The Dark Side of China’s Solar Boom

SHANGHAI — China’s solar industry ambitions can be best seen from outer space.

The Longyangxia Dam Solar Park in the northwest province of Qinghai is the world’s largest such park and underscores the country’s grand aspirations. In total, 4 million light-absorbing photovoltaics (PV) panels stretch across 27 square kilometers — roughly 13 times the area of Monaco — of the arid Tibetan plateau, producing enough electricity to light more than 200,000 homes. The park and other projects — like the world’s largest floating solar farm in eastern Anhui province — are part of China’s clean energy revolution, as it shifts from one of the world’s worst polluters, to a country enthusiastically adopting clean energy as part of its “war against pollution.”

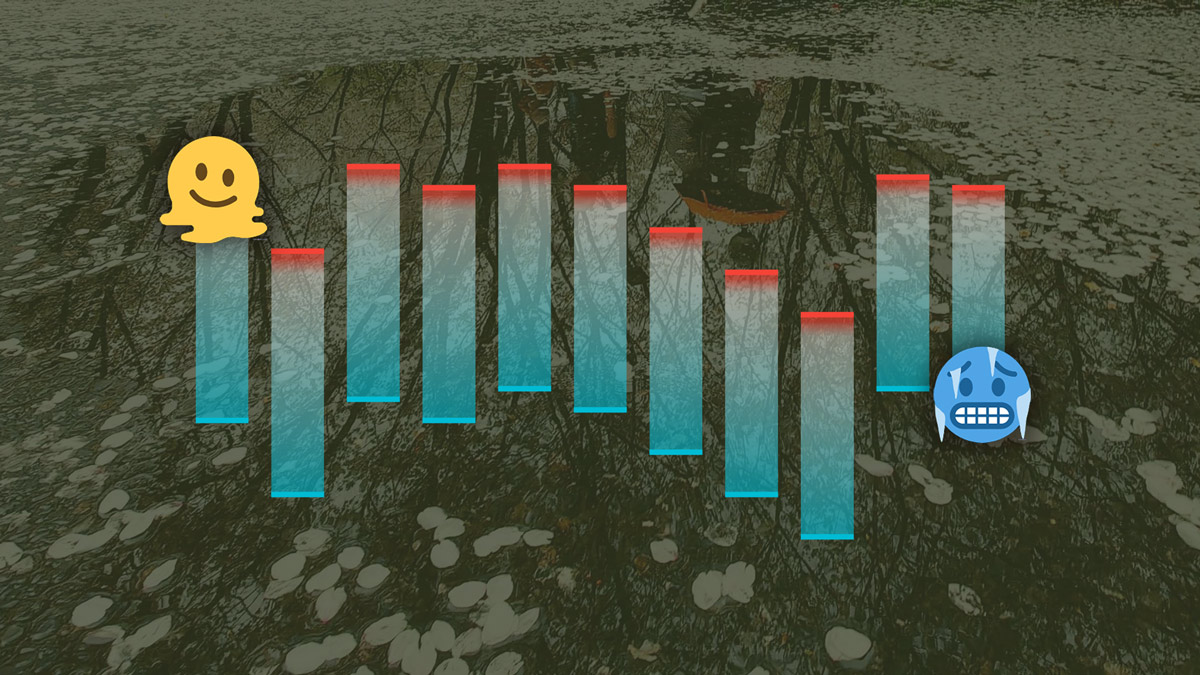

China is now the world’s biggest solar market in terms of money spent, panels manufactured, and energy produced. But despite the country’s sunny outlook, there are dark clouds looming. PV panels, which convert solar energy into electric energy, have a lifespan of around 30 years. Experts say that millions of aging panels could have significant environmental impacts — especially since China doesn’t have specific regulations on solar panel recycling. The International Renewable Energy Agency predicted that by 2050, about 20 million tons of PV panel waste could be accumulated in China — the largest amount of solar trash worldwide. And according to a 2018 study from Tsinghua University’s School of Environment in Beijing, the panels have been piling up since 2015.

In short, the solar industry could be “a ticking time bomb,” the general manager of a Chinese company that collects retired panels told the South China Morning Post.

Mary Hutzler, senior fellow at the Institute for Energy Research in Washington D.C., said that solar panels are manufactured using hazardous materials — including sulfuric acid and phosphine gas — making them difficult to recycle. They also contain toxic metals like lead, chromium, and cadmium, which can be harmful to humans and are likely to leak from electronic waste dumps into drinking water supplies.

“It is very important to initiate public discussion right now, so that proper processes can be developed and implemented in time to ensure that the upcoming decommissioning of these products is done properly,” Hutzler, who was also a former energy analyst for the U.S. government, told Sixth Tone. “Failure to do so will result in additional threats to public safety and health and the environment as a consequence of major governmental commitment to these supposedly clean forms of energy.”

Most policymakers in China, as well as in other countries, are unaware of the problem — though some manufacturers are beginning to look into it, Hutzler said.

According to Paula Zhang, corporate communications manager from one of China’s top PV producers, Trina Solar, China is setting up projects to research solar waste, though she didn’t elaborate on them.

The world’s solar industry is currently dominated by silicon-based PV panels. While 90 percent of the materials used in them are nonhazardous, the remaining toxic elements can be a problem when recycling. Last month, Europe’s first PV panel recycling plant began operating in France, repurposing all of the materials from the panels to make new solar panels. In the past, the panels were recycled in glass recycling plants, and only the glass and aluminum components could be recovered.

But in China, no recycling facilities are in sight, despite the government's push to promote solar energy. China’s switch to solar is part of its plans to combat air pollution and a critical step in meeting its Paris Agreement targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. China is halting construction on new coal-powered plants that emit the hazardous pollutants that often choke cities in a thick blanket of toxic smog.

At a three-day international solar panel exhibition in May, hundreds of solar panel manufacturers and buyers convened in Shanghai. In a party-like atmosphere, with free beverages, blinding lights, and thumping music, producers advertised the latest developments in the world of solar energy. The celebratory atmosphere of the industry’s progress appeared unaffected by the prospect of unmanageable waste, and several exhibitors Sixth Tone spoke to said that they were unaware of the issues associated with solar refuse.

Trina Solar — which was at the exhibition — has recycling policies, according to communications manager Zhang, though she didn’t elaborate further on the topic. Trina is also one of a handful of Chinese companies researching solar waste, as noted in the Tsinghua University study. Zhang acknowledged some of the the panels’ environmental impacts, but added that cadmium and lead only account for less than 0.1 percent of the panels — not the 1 percent stated in the Tsinghua study. “Cadmium and lead are indeed harmful for the environment, but it depends on their quantity — if we’re talking about 0.1 percent, then it’s almost negligible and unharmful,” she told Sixth Tone.

The urgency of solar panel recycling hasn’t yet dawned on most manufacturers. In China, expenses related to the handling of solar panel waste disposal or recycling aren’t factored into production costs. That’s different from Europe, where a directive requiring producers to take responsibility for recycling the panels they sell has been in place since 2012. In China and other Asian countries — including India, where solar projects are also taking off — similar policies are yet to materialize. Currently, only certain components can be reprocessed in China, but particular components deemed harmful aren’t recycled, authors from the Tsinghua study note. “The 25-year life of the component is only the marker of the panels’ guaranteed lifespan; in fact, many components can last more than 25 years,” Zhang from Trina Solar said.

There could be a big payoff for getting a head start on recycling. According to international consulting firm Global Market Insights, there’s “a huge untapped potential” for a solar panel recycling industry. The global solar panel recycling management market is likely to be worth $360 million by 2024, with the Chinese market exceeding $50 million.

But one of the biggest challenges is convincing the different parties involved in the solar energy ecosystem to actively spearhead and participate in recycling initiatives sooner rather than later. At the Shanghai exhibition, many sellers and dealers said that they operate within the current regulations. A representative from Sungrow Power Supply Co. Ltd. — which runs the floating solar farm in Anhui — pointed to the environmental section of their corporate social responsibility handbook and said that all recycling-related questions should be directed toward the manufacturers.

Experts studying the subject have long been critical of such lenient attitudes and the snail-pace approach in the midst of such a dramatically expanding industry. Greenpeace’s climate and energy campaigner Cai Jingwen told Sixth Tone that while solar energy comes with significant environmental and economic benefits, there’s a strong need for policies and guidelines that mandate solar panel recycling.

Peng Peng, general secretary of the China New Energy Investment and Finance Alliance — a nonprofit that helps connect renewable energy organizations — compared solar waste to the peak of the electronic waste problem between 2010 and 2015. Just as how China introduced rules on electronic waste — stopping it from becoming the dumping site for the world’s toxic electronic scraps — Peng believed that China could do the same before solar waste becomes critical in 2030.

Meanwhile, Hutzler, the senior fellow at the Institute for Energy Research, said that policymakers need to think about future problems, not just renewable energy advancements. She said the issue of solar waste is “significant” and needs to be addressed — something which isn’t currently happening in most areas of the world.

“No form of energy in its modern use is wholly clean,” Hutzler said. “There are always tradeoffs, either in the production of the product or its consumption.”

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Header image: Sheep wander behind solar panels in Gonghe County, Qinghai province, May 30, 2018. Sun Rui/CNS/VCG)